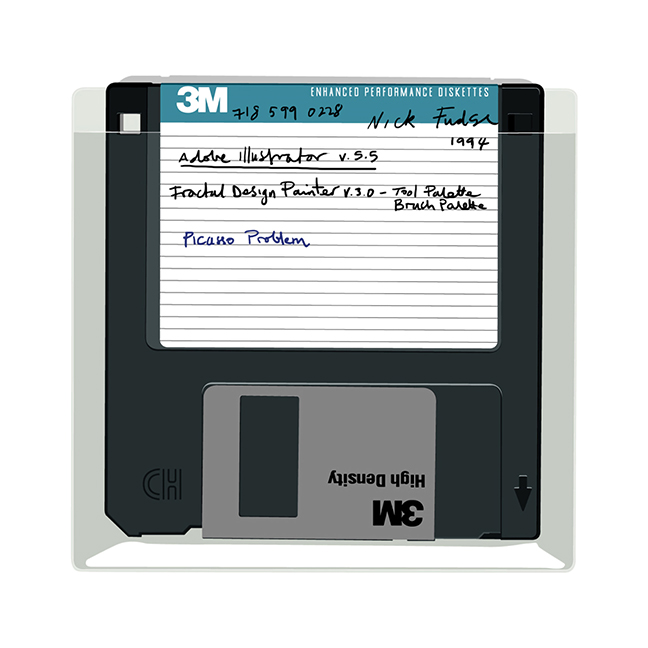

Aria Content Series: Nick Fudge

Nick Fudge, Self-Portrait with Gaultier Sunglasses, Painted Desert, U.S.A., 1994-

About the artist:

Nick Fudge, a Young British Artist (YBA) from London, UK, is widely recognized for his rebellious and enigmatic approach to art. Nicknamed a "rebel" by Jack Malvern of The Times, Fudge built his reputation by defying convention. He famously destroyed his work at Goldsmiths on the eve of graduation and later secretly worked on digital projects that anticipated entire fields of digital materialism and media archaeology.

A pioneer of digital art, Fudge was among the first artists to incorporate core desktop technologies into his work. He allegorized Adobe Photoshop's transparent layers, macOS Chrome, custom vector GUIs, timeline interfaces, and user command structures as foundational materials. By the mid-1990s, he was integrating editing languages, interface logic, and file architectures into his art. This predated the widespread recognition of media archaeology by at least five years, and he explored digital materiality nearly a decade before it became a central focus in art discourse. Fudge’s recursive, hybrid digital practice anticipated many of the concerns that would later define “post-Internet art,” developing these themes more than a decade before the term entered the mainstream art lexicon. Grounded in conceptual rigor and technical experimentation, his approach gives his body of work a unique resonance in today's environment, where the history and future of digital art are constantly negotiated.

Fudge’s digital oeuvre is a living Digital Boîte-en-valise—recursive and always in flux—that eschews static final outputs for continuous editing and conceptual iteration. In line with Duchamp’s call to work "underground," Fudge withheld his digital works from exhibition for over two decades, using this creative obscurity to experiment with emerging software and cultural forms. Trained as a painter, Fudge brings an acute sensitivity to medium specificity, treating digital files as autonomous materials—unprinted, unflattened, and fundamentally original. This stance, decades ahead of the NFT market, renders his digital corpus genuinely collectible in the present crypto era.

Recent highlights include his conceptual digital intervention in the Lop Nor Desert in China—a project that was not shown to an audience, but was documented as a landmark event in his digital practice—and an ongoing confidential art/science tech collaboration with partners in Beijing. Fudge’s work remains a touchstone for artists and theorists interested in the recursive life of digital art, the poetics of the ‘image’, and the ever-evolving relationship between image, interface, and the artist’s Digital Boîte-en-valise.

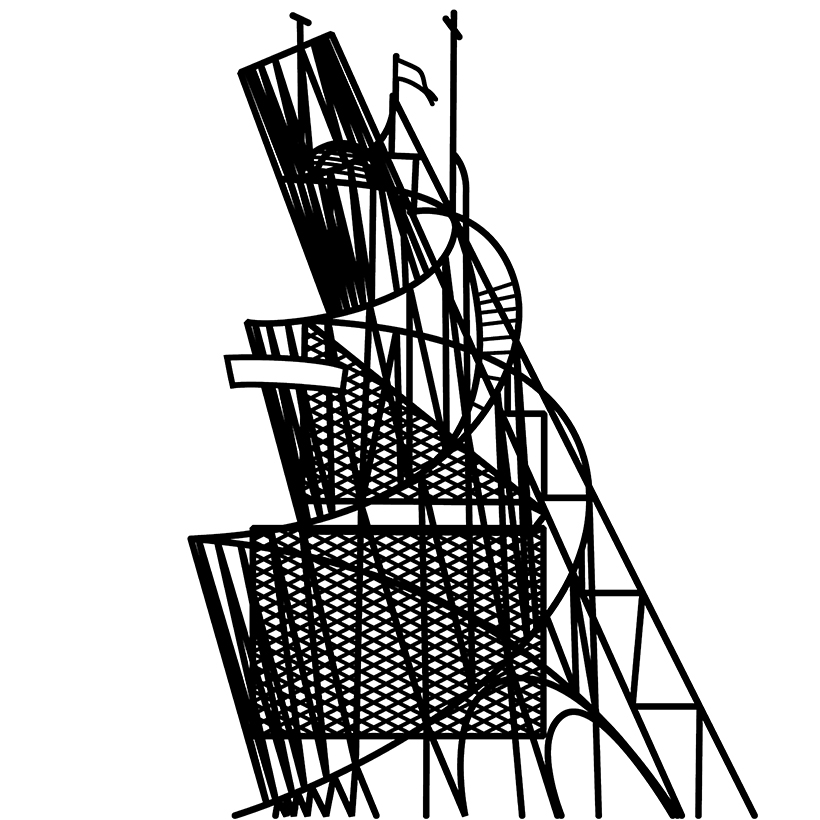

Nick Fudge, Livre de Hasard (Autoportrait Mécanisme), 1994–

The Interview:

Written by Paloma Rodriguez

Interview Questions:

Paloma: You famously destroyed your Goldsmiths work and later worked “underground” for more than two decades. How has this long period of intentional obscurity of working without exhibition pressure shaped your understanding of visibility, authorship, and artistic legacy?

Nick: I don’t think of destroying my Goldsmiths work as a dramatic gesture so much as the first move in a long experiment, influenced by things I’d absorbed from artists and writers such as Duchamp and Mallarmé. Duchamp’s advice to young artists to “go underground,” his chess games, the Monte Carlo Bond and his interest in roulette; Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés; and Cage’s chance operations all suggested to me that art could involve genuine risk, not just stylistic risk. As gambling had played a significant part in my early life, it made sense to me that, in order to discover genuinely new forms, an artist might need to take a significant risk by disappearing completely. Instead of moving straight into the gallery system, I chose to work “underground” for over twenty years. That decision immediately changed my sense of visibility: I wanted to see what would happen if I stepped outside the normal circuits of attention and gave myself space to define my own conditions of freedom, and to weigh offers and opportunities carefully rather than automatically entering a career pattern.

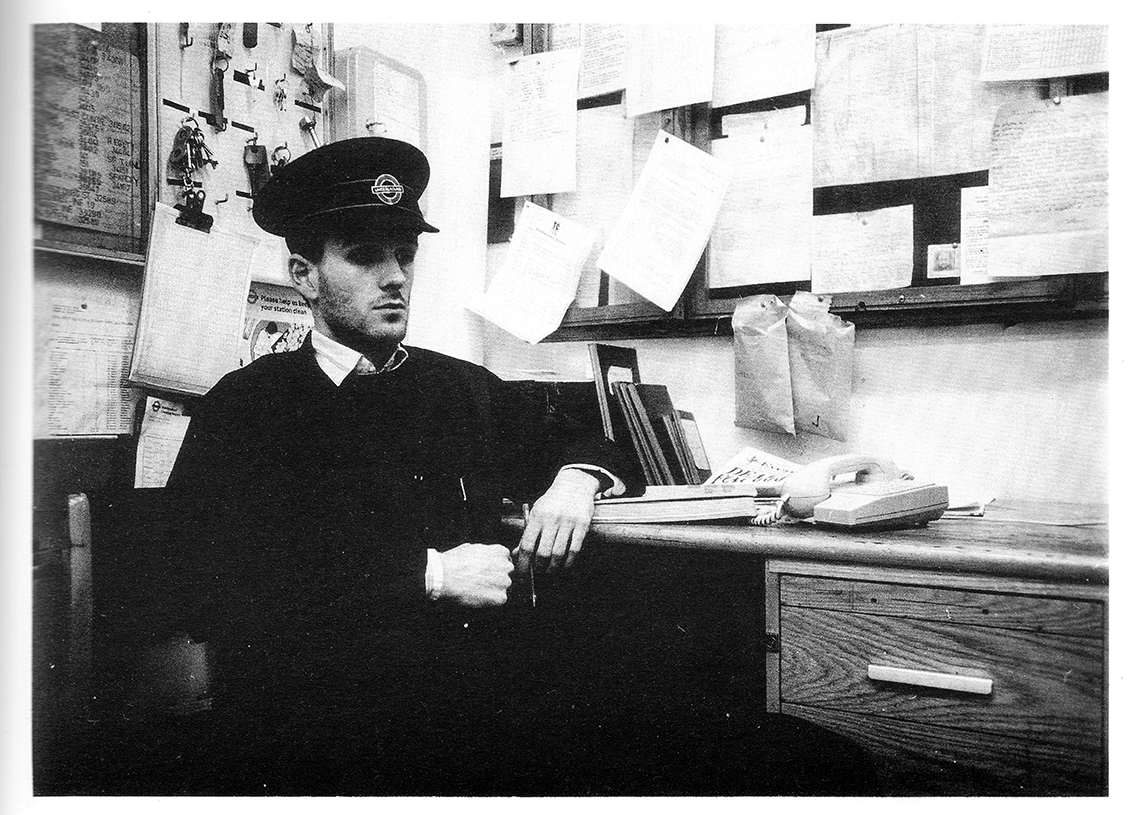

Nick Fudge, Self-Portrait in Uniform, London Underground, London, England, 1988.

Following on from Goldsmiths, I left the UK and travelled across America; and, for a while, chose freedom over both career and art - making work only intermittently and living a kind of romantic, hand-to-mouth Beat-like life on the road. It wasn’t until I encountered computers in Philadelphia in 1992 that I felt a strong pull back to making art seriously. Initially, I was more interested in finding new forms of painting than in “digital art” as a genre. I wanted to push painting beyond canvas and brush, to see what would happen if its languages and processes were explored across screens, interfaces and GUIs, and their version histories – archived not in the white cube but on external hard drives instead. In practical terms, that meant treating the computer not just as a tool but as a place where painting itself could be redefined: using vectors, rasters, layers and windows in the same way earlier painters had used colour, texture and composition – I created my own interfaces, desktop spaces and custom tools, and used them to construct visual metaphors – allegories of the digital systems that produced them. Allegory, after all, always carries a double meaning—it points to what can’t be said directly. I realised I could make digital paintings that did the same: hiding complex ideas in plain sight, within the everyday language of the interface. I kept this work completely out of circulation. Working without exhibition pressure meant that authorship became, for me, less about public recognition and more about having creative freedom - to immerse myself within this new medium and to explore the exquisite tension between success and failure. This had nothing to do with sales or reviews, and everything to do with whether the work continued to raise interesting questions.

Over time, that choice changed the way I thought about visibility. Not exhibiting my work no longer felt like a lack and started to feel like an active decision — a quiet form of resistance. Since I had no exhibition deadlines or public expectations, I could go back to the early files again and again, rewriting, reconfiguring and creating new versions. Gradually, the entire body of work began to feel less like a set of singular digital objects and more like one interconnected system. I eventually named this larger structure the “Digital Boîte-en-valise,” after Duchamp’s portable museum — my own digital, portable version of assembled artworks. This updatable collection of digital objects challenged

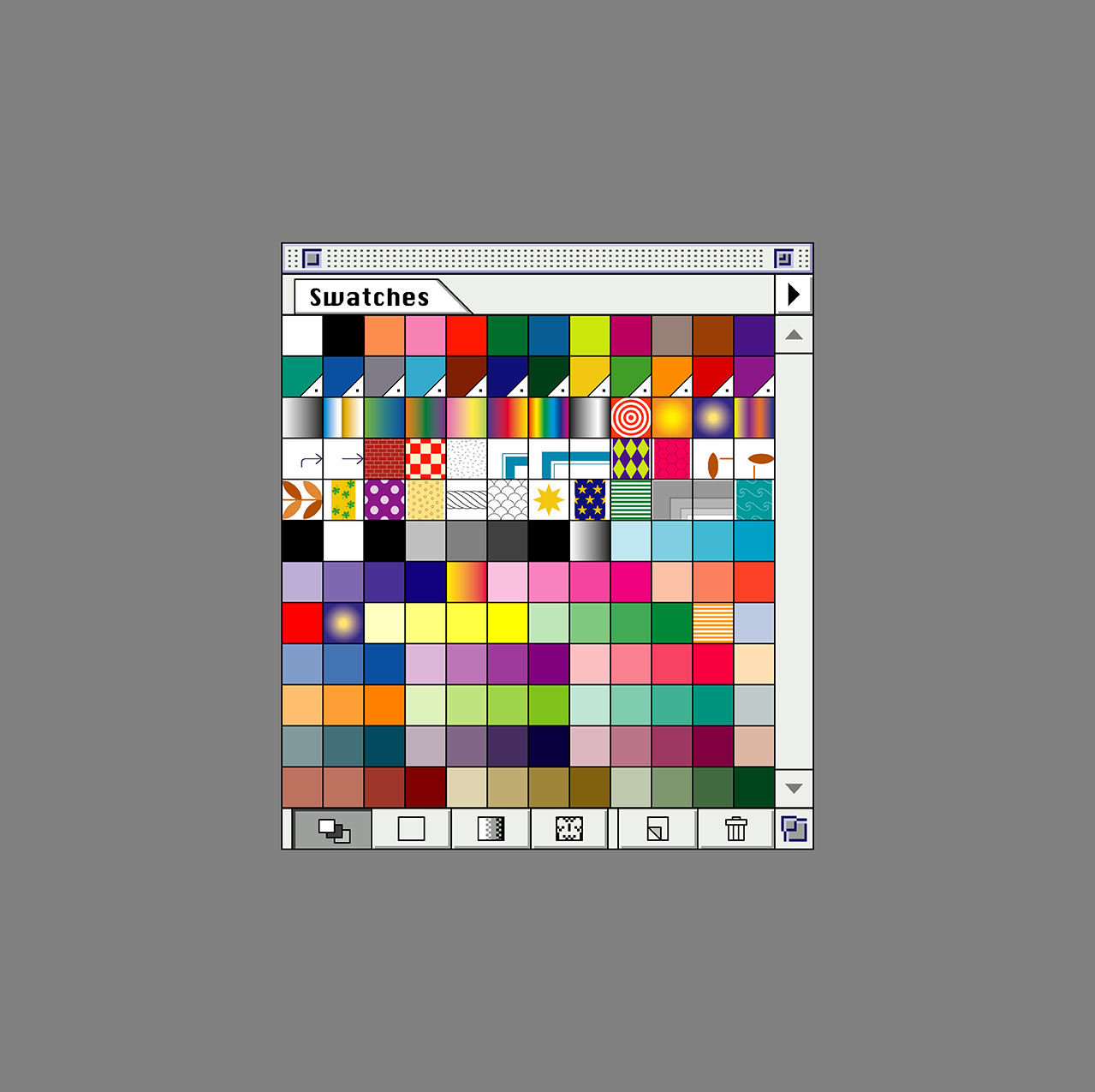

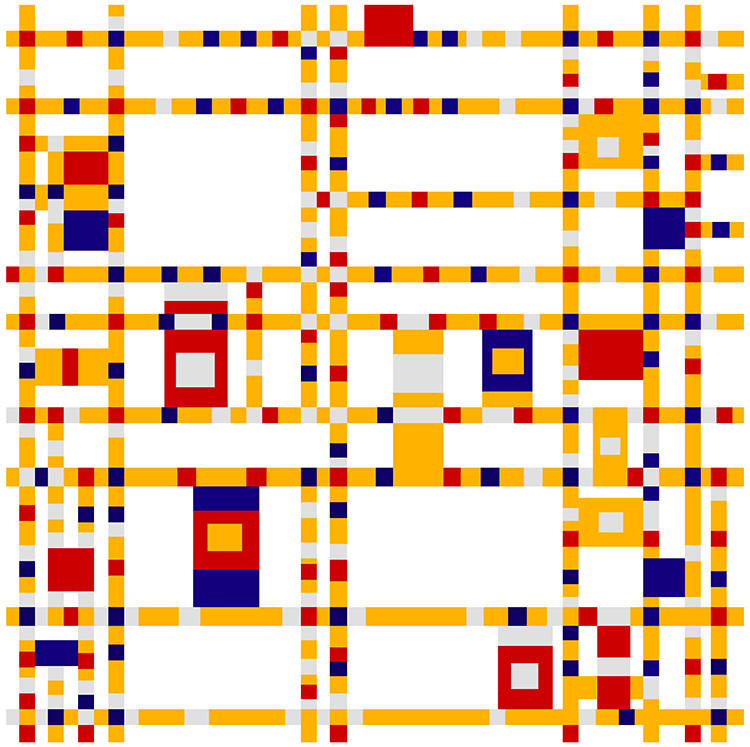

Nick Fudge, Swatches Palette on a Gray Field VII, 1994–

Macro-series: Desktop of Perfect: System Palettes. Sub-series: Digital Faktura: Toolboxes & Swatches

Nick Fudge, Monument Valley, 1994–

me to speculate: if the work keeps changing, where does the ‘artwork’ exist within the digital realm? As a single image, as a series of images, or as a set of files? What happens to these artefacts over time? Working without a gallery schedule forced me to confront these questions, because there was no sales context or gallery schedule to define this for me or determine when the work was ‘complete’.

These experiences shaped how I think about authorship and legacy. For me, authorship is less about being a visible name attached to a finished product, and more about its ‘death’ - as art production has increasingly become a medium or a window for reflecting and framing collective thought over individual concerns. This is something that has only deepened in the age of AI - where the authorial gesture of an individual has become endlessly complex. Artistic legacy is likewise not just a list of exhibitions or a linear career narrative; it is about whether the structures I built during that long period of obscurity can generate culturally significant trajectories now and in the future.

“In a culture where many people feel they must play by the existing rules of visibility, my underground years showed me that an artist can, at least to some extent, decide how, when, and even if their work appears – and that this choice fundamentally shapes what visibility, authorship, and legacy can mean.”

P: Your return to public visibility in 2016 prompted renewed interest in the YBA legacy and the artists who diverged from it. How do you relate to the YBA label today, and what do you feel that generation got right or perhaps might have misunderstood with regards to YBA as well as your relationship with it?

N: I’ve always had an ambivalent relationship with the YBA label. On the one hand, it’s a useful moniker; on the other, it reduces a very complex period to something akin to a logo. The lived reality was much messier, with competition fuelled by tutors and students alike becoming an incendiary flame. It is hard to say what was ‘right’ and what was ‘wrong’ about it. It was both world-changing and highly challenging. To explain this a little more, I will perhaps have to share some stories. When I was a first year student, on day one, I intuited there was something in the air and went around drawing large penises on the other first year students’ studio walls as an opening gambit. One year later, when Damien (Hirst) was a first year student - he already knew that we all could take over the art world by storm and would frequently visit my studio (and probably the studio of other students) and say ‘hey - that’s great, you should take that down to Cork Street’ - whereupon I (a naive idealist) shrugged and would say ‘nah’ and air quote Beuys's ‘Kunst = Kapital’ back at him - knowing he respected Beuys deeply. It was hard not to be impressed by Damien’s ‘balls’.

During my third year, Jon Thompson, the Head of Art at the time, grabbed me, Mat (Collishaw), and Damien to show our work to the first years: I with my Leonardo oil paintings on soap, Mat with his works of porn, and Damien with brightly painted saucepan ‘spots’ hung on the wall (a prototype of his later spot paintings) - worked as a sort of trial-by-fire to shock them. Needless to say when we left the seminar, Jon was rubbing his hands together and chuckling and said: ‘job done’. It was such a rare time where most of us (the students) - who were from working class backgrounds - were exposed to revolutionary thinkers, ideas and a myriad of opportunities that passed through the college.

Damien Hirst interrupting one of my photo shoots, Goldsmiths’ College, London.1987. Photo: Nick Fudge

Nick Fudge, Discovery of Criticism Number Four (After Leonardo), Oil paint on heart-shaped soap, 1987. Goldsmiths.

By my final year, the environment was one where crits took on an environment of intellectual warfare - where students and faculty would hash it out no holds-barred. Micheal Craig-Martin would counterbalance this by taking groups of us into a private space where he would uphold each students’ work with his intense intuitive focus in a way that gave us permission to realise who we were as artists and to forge our own unique paths - it felt like a sort of magic at the time. However, by the time I graduated in 1988, TV cameras and the press began arriving on campus, Frieze was about to take place and I just felt there had to be another way - so I burnt my work and left the UK behind for the American deserts where my work, while not taking place within the YBA trajectory overtly, grew underground alongside it.

When I talk about my work to collectors and curators now, I am often asked - ‘how did you get away with it all’? This helps me to return to your question about how I relate to the term YBA presently. I think it is important to point out that the stories I have mentioned above are really just trying to give an account of the types of experiences that shaped us as a generation of artists and why we were okay with risking everything. Some were tragic casualties of such risks, I am reminded of Angus Fairhurst and Joshua Compston. It wasn’t only artists of course who were willing to risk and take matters into their own hands to build something new - young and up-and-coming gallerists/dealers were also willing to take risks on unknown artists straight from their BA with no guarantee on sales and perhaps even making a loss - Karsten Shubert, Paul Stolper, Sadie Coles, White Cube, City Racing, Factual Nonsense, The Showroom, Fruitmarket Gallery, etc., were all essential in making the movement possible. This is what was ‘right’ about the YBA movement - that it came together out of everyone doing it themselves and also taking risks. The fact that some of these gallerists are now blue chip and Goldsmiths is a brand developed from the YBA movement is what has become wrong about it - as artists like myself and my classmates would never even be admitted to universities like Goldsmiths now… galleries are not taking the risks they used to either. This just creates a conservative environment of stasis for all. Digital platforms and AI have the potential to take us somewhere out of this situation - but I can talk about that in your next question.

What is of interest now is the wider ecology of artists who maybe (like myself) were not the central focus, but nonetheless were at its heart - who have all forged their own paths, but have still yet to be fully appreciated, artists such as: Lala Meredith-Vula, Anna von Gwinner, Dermot O’Brien, Simon Patterson, Hamad Butt, Derek Mawudoqu, Jeremy Akermann, Simon Gales, Micheal Stubbs, Phil King to name only a few. Going forward, I am very happy to see renewed interest in this moment - which is opening opportunities for discovering its less visible artists. The term YBA is one that still stands for an approach to art-making that is bold, rebellious, that shakes things up, satirises, and refuses to conform to corporate culture, that preserves artistic freedoms for the artists themselves. Long may it live in the face of difficult times such as those we face now.

So I don’t reject the YBA narrative outright, but I do want to expand it. Alongside the familiar story of rapid fame and market spectacle, there’s another layer: people who went underground, moved countries, changed mediums, or only became legible much later. I’m part of that layer – the negative space around the label – and I think that’s where a lot of the interesting questions about visibility, authorship and legacy are still unfolding.

P: You’ve described Sedition as the “fitting first platform” for your re-emergence, partly because it respects the ontology of digital material. How has making your work public through Sedition changed the way you think about circulation and visibility?

Nick Fudge, Reality Drive_06_2, Destruction of Appearance collection, Sedition, 2023.

N: When Sedition invited me to be a curated artist on their platform, it felt like a fitting return because they understood something essential: digital art isn’t a reproduction of something else. It is the work. When I first joined, the platform was already about 12 years old and going through a quieter period. Now, under Dyl Blaquiere, it is actively using “networks” in every sense of the word – connecting with new collector communities, collaborating with other platforms such as Aria, and partnering with companies like Muse Frame that extend artists’ visibility and how work can circulate globally. Instead of one annual show in a single gallery, an artist can now appear on multiple platforms at once, with screenings and events throughout the year. That changes not just where work is seen, but how artists are supported – through broader collector bases, shared PR, and overlapping communities.

This expansion of networks and exhibition/event possibilities via Sedition's platform has also changed my engagement with audiences, collectors and digital artist communities. A collector on Sedition isn’t necessarily someone embedded in the traditional gallery system; they can be anywhere in the world, with very different backgrounds. Through Sedition, my collector base has grown to include collectors from Mexico, USA, UK, India, etc., and also have people follow the work in a way that isn’t like social media at all, but driven by genuine interest in the art itself. At times the platform feels like it's going more towards a web 3-like model where artists grow like-minded communities, collectors support artists and can mint works as NFTs if artists agree. That shifts visibility away from the traditional gallery model of spectacle and critical mass. It becomes, instead, a form of informed distribution and expanded encounter – via online, often telematic events occurring across the globe at the same time - but in different time zones.

You no longer have to build massive physical structures to be seen as an artist. The complexity and reach of the system itself – its archives, metadata, collector communities, and links to external networks – can generate multiple forms of visibility. In that sense, Sedition mirrors some of

Nick Fudge, Cubist Pure Data, Household enamel and metallic paints on canvas. Dimensions: 168 x 128 cm / 66 x 53.3 inches. 2003

Nick Fudge, Pure_Data_2, 1994–

Nick Fudge, Pure_Data_Breve_5 (still with AI incorporation), 1994–2025, Sedition, 2025

my own philosophical and material concerns - from artworks as virtual objects, to nodes on a network, to streaming worldwide - Sedition is a globalised system rather than a fixed institution.

With the rise of AI and hybrid platforms, I’m increasingly interested in how my work can help visualise those systems – how it can give audiovisual shape to the logics and behaviours of AI itself. This changes how we imagine what AI is and what it could become. A good example of this is Mat Collishaw’s recent work on Sedition, where -from his long-term engagement with AI - he has generated these natural–artificial hybrid creatures that feel uncanny in their mimicry of nature and natural behaviours, but are ultimately unnatural and somewhat monstrous - as they tap into the infinite morphability and black-box unknowability of it all. It’s a kind of theatre of machine learning processes framed and staged for human perception.

Left: Nick Fudge, RGB Calibration (after Jasper Johns), 1994–2023, Sedition, 2023 (clip).

Right: Nick Fudge, RGB Calibration (after Jasper Johns), 1994–2023, Sedition, 2023 (still).

As Sedition started 15 years ago, it has built an extraordinary roster of artists, many of whom are now working at the frontier of what’s possible with AI. That makes it exciting for me to belong to its community – and I’ve also made many new friends along the way. If the YBA moment was defined by artists taking over derelict buildings to create their own spaces, then perhaps this new era is defined by artists occupying and reshaping platforms: using them to become visible on their own terms, to form networks that aren’t tied to one city or one market, and to build communities that are experimental, dispersed, and still deeply connected.

P: Given your long-standing interest in digital materiality and the poetics of the file, how do emerging questions around authorship and provenance in the age of AI shape your understanding of your own work? Do you view AI as a tool, a threat, or a new kind of distribution logic that reframes what it means for an artwork to originate from a particular artist?

N: I don’t see AI as a sudden break with the past. For me it’s more like the latest layer in a set of questions I’ve been working with since the 1990s such as: what happens when the very idea of an “image” falls apart? From very early on, my digital practice wasn’t about making singular images. I would keep returning to the same files over years, making new versions and iterations, which raises a simple but quite deep question: if a work keeps changing, which version is the artwork? The first one? The most recent one? Or the whole chain of changes over time (now referred to as metadata or blockchain)? For these, and many other reasons, I refused to exhibit my work for two decades.

In addition, I have always resisted the pressure to upgrade constantly. I still

use software and hardware that are considered obsolete, including Adobe Illustrator 8.0.1, because I

don't accept that older tools should automatically be abandoned. I treat it as an experiment to explore

how long I can keep producing vector works with this version - and what does it mean that it still remains

sufficient for my purposes? Working with these early tools is a quiet form of resistance to built-in

obsolescence, and at the same time it keeps files from the 1990s ongoing in the studio - rather than as

frozen relics.

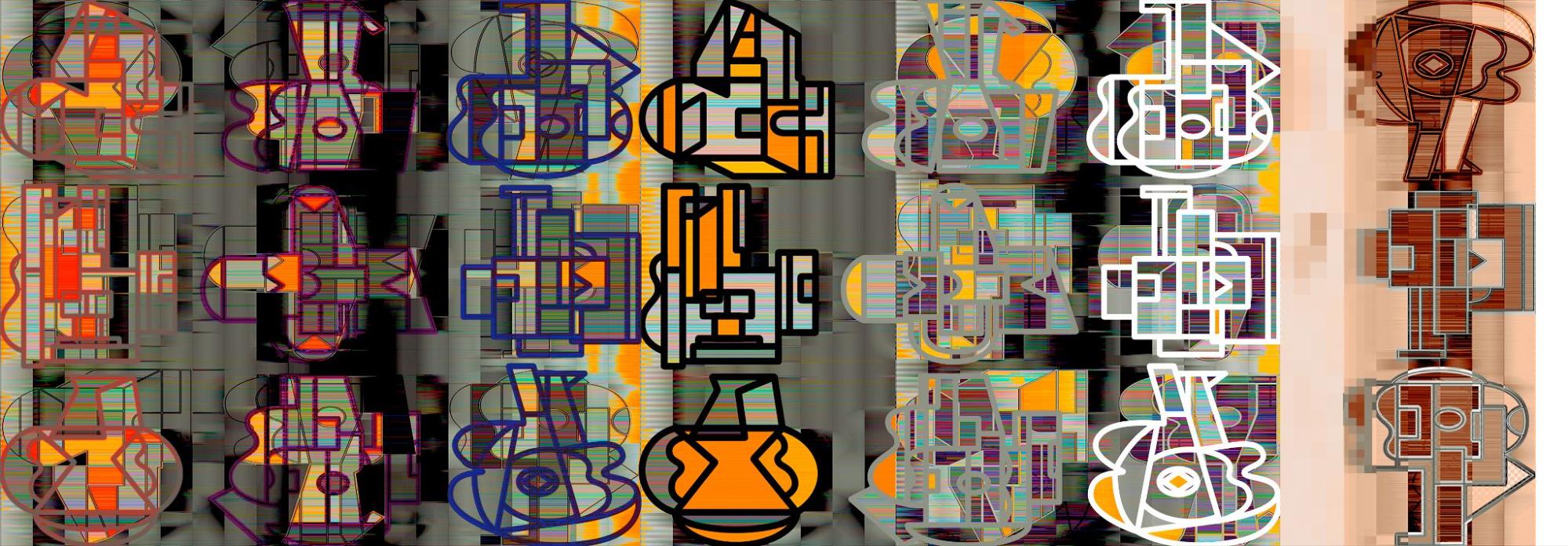

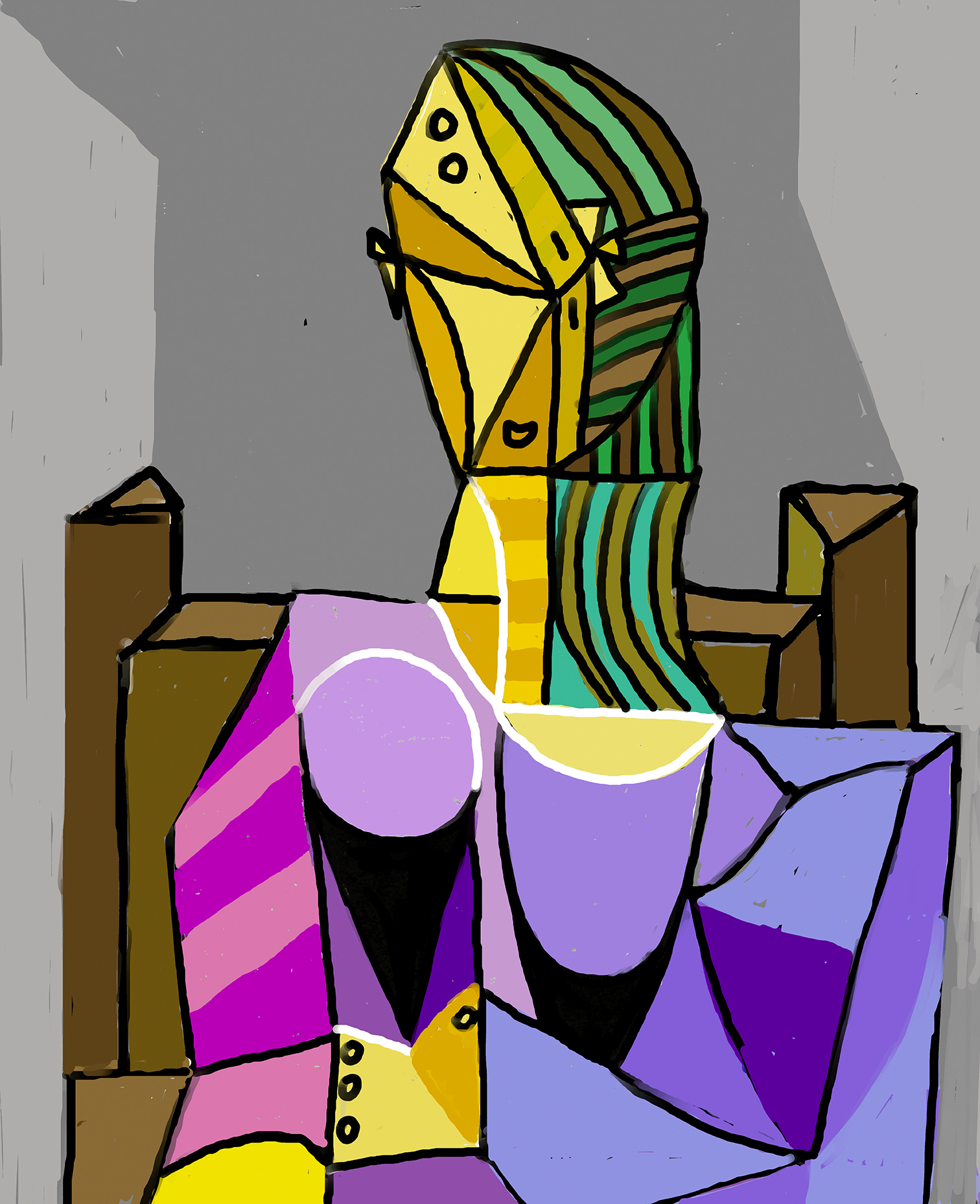

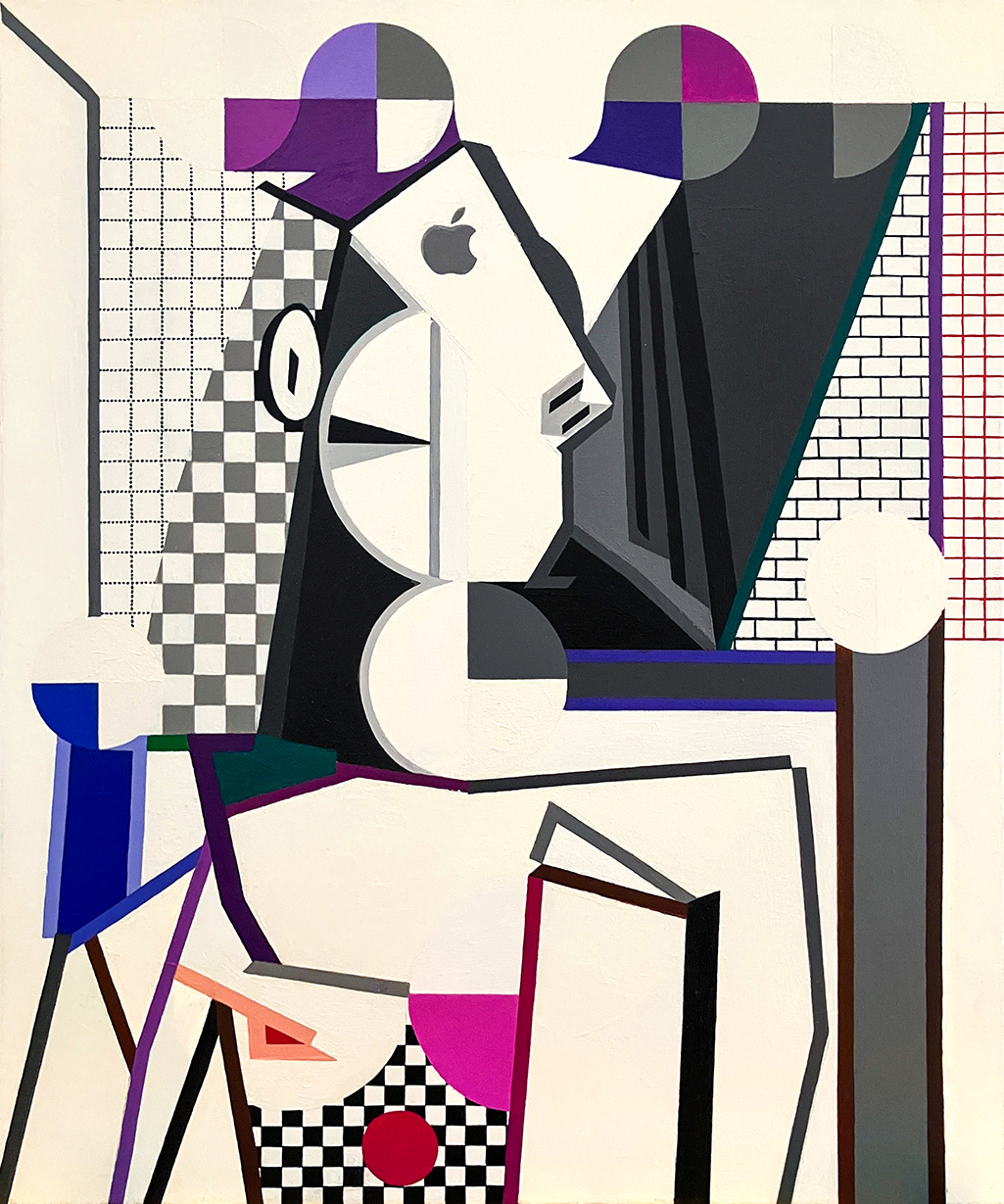

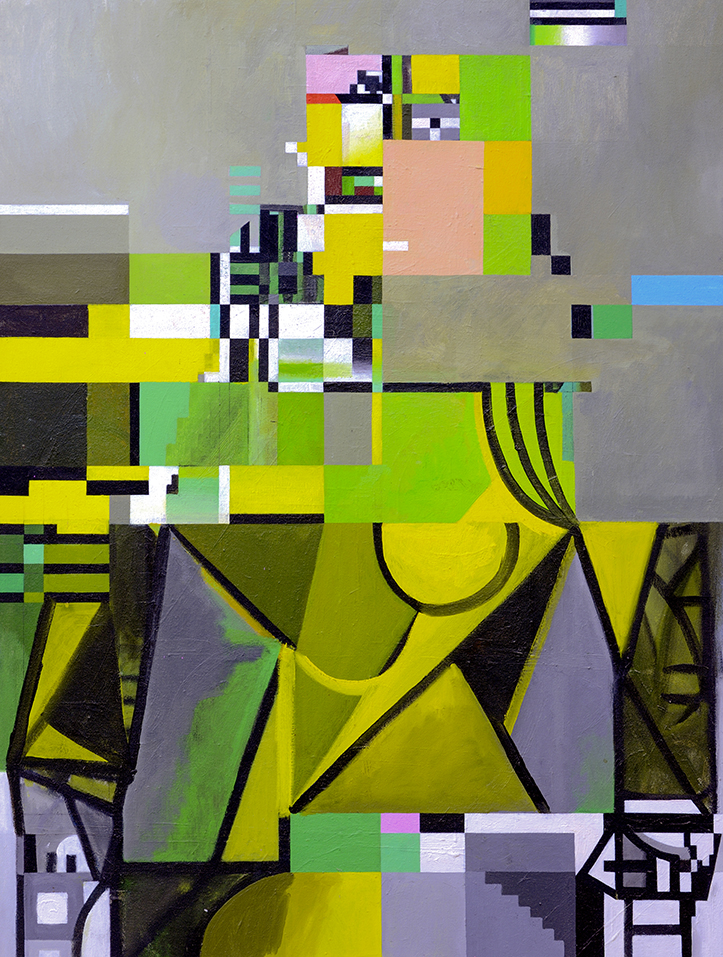

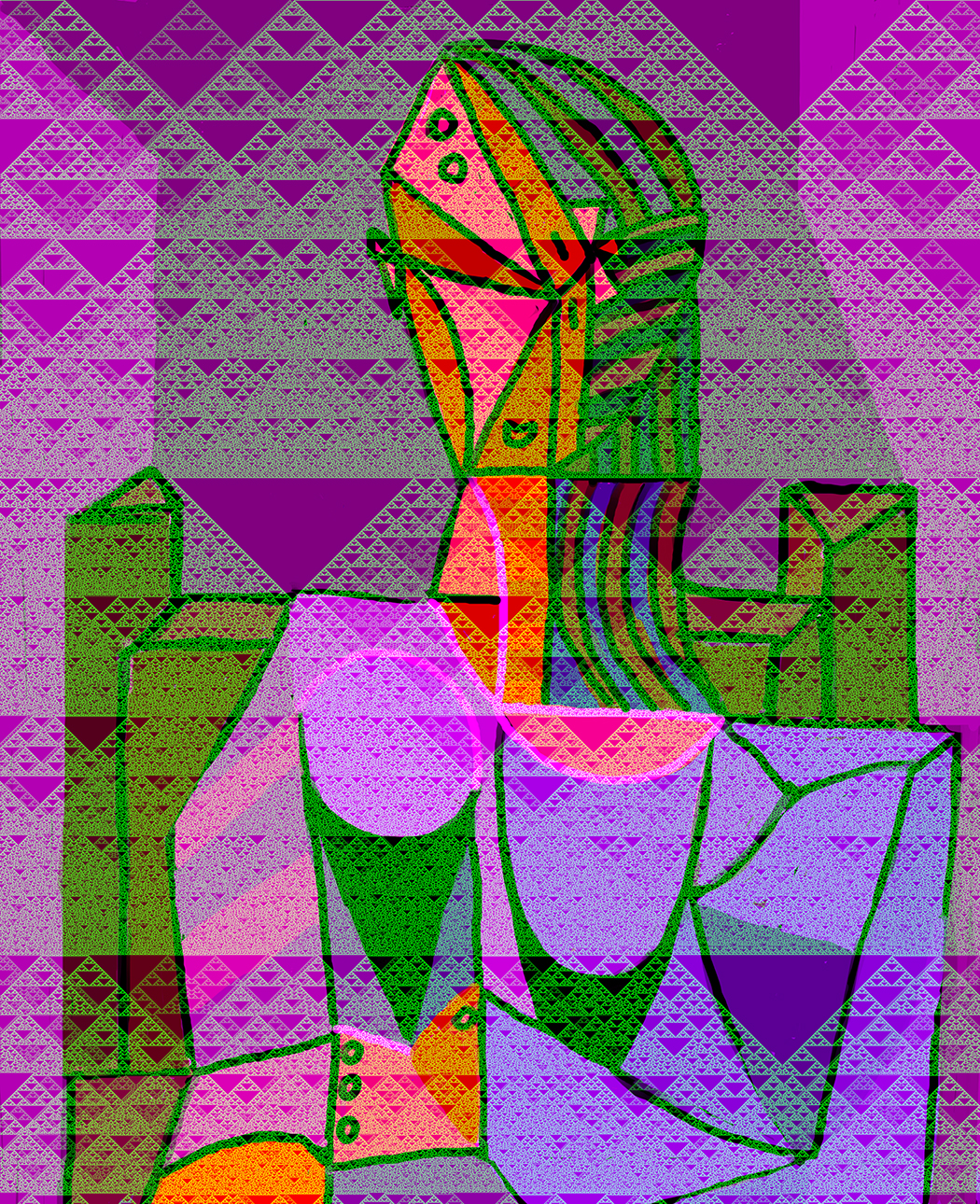

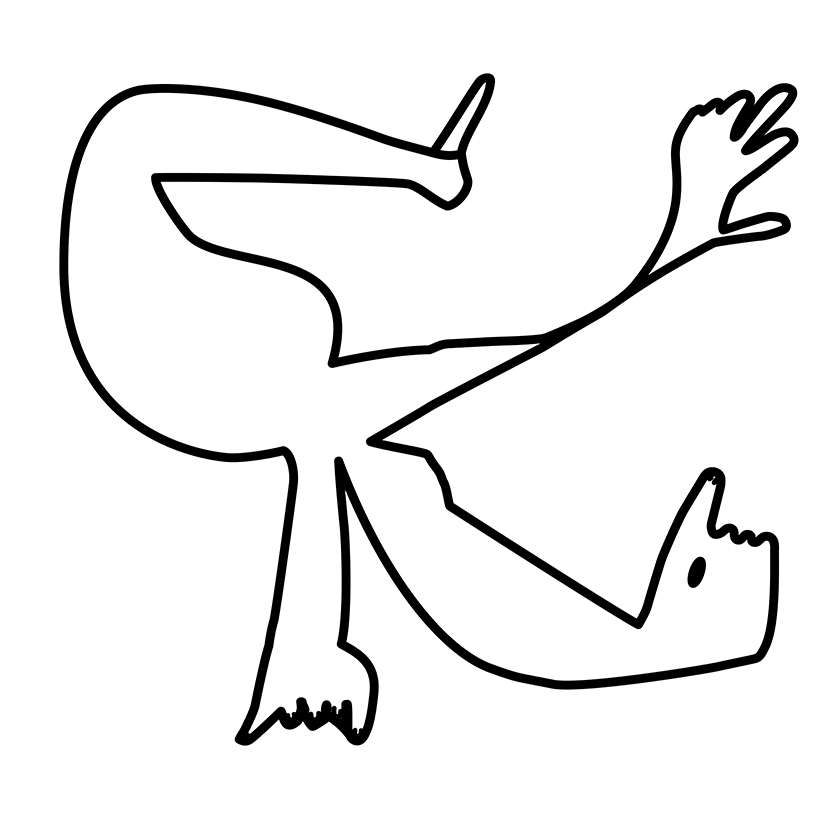

Top Left: Nick Fudge, Picasso Problem: Seated

Woman (5), 1994–,

Top Right: Nick Fudge, Think Different (After Picasso), 2019 -2024. Oil paint on canvas: 60.3 x 50.1 cm / 23.75 x 19.75 inches

Bottom Right: Picasso Blue (OS 7.0), 2012-2018.Oil paint on canvas, 101.2 x 76.1 cm / 39.8 x 30 inches

Bottom Left: Nick Fudge, Picasso Problem: Seated Woman (5x Variant in CA Green), 1994–AI–2025

Now, when I use AI, I integrate it into my broader archival ecosystem - which also includes my archive of physical paintings - such as those in the Pure Data series discussed in the previous question - as well as in the Picasso Problem - Seated Women series shown in the images directly above. Rather than prompting it to scrape the internet for new material, I use it to re-encounter my own archive. I'm interested in treating it as an intervention device that I can use to discover variants and mutations that weren’t possible with the original software I used in the 1990s and 2000s. In some cases, this makes the image feel like a 'quantum' image in that it belongs to both its original moment and the present moment simultaneously, as if the past file has been quietly updated from the future.

Nick Fudge, Old Master Gan (still with AI incorporation), 2024–2025

I think that by using AI to create images, we have crossed a threshold where there is no longer a shared understanding of what constitutes an image. What we still call images are often just frames in a data stream — the outputs of pipelines, and algorithmic systems we don’t fully see. Through a kind of perverse logic, AI is starting to function as a new religious order that organises all of this — an invisible norm that tells people what is probable, plausible, visible, or real. My work doesn’t celebrate this shift; it attempts to visualise it - to make it legible and show what it means to appear to be working with ‘images’ when the old idea of the image has gone, and where the new organising principle is a machine that people increasingly trust to ‘see’ on their behalf.

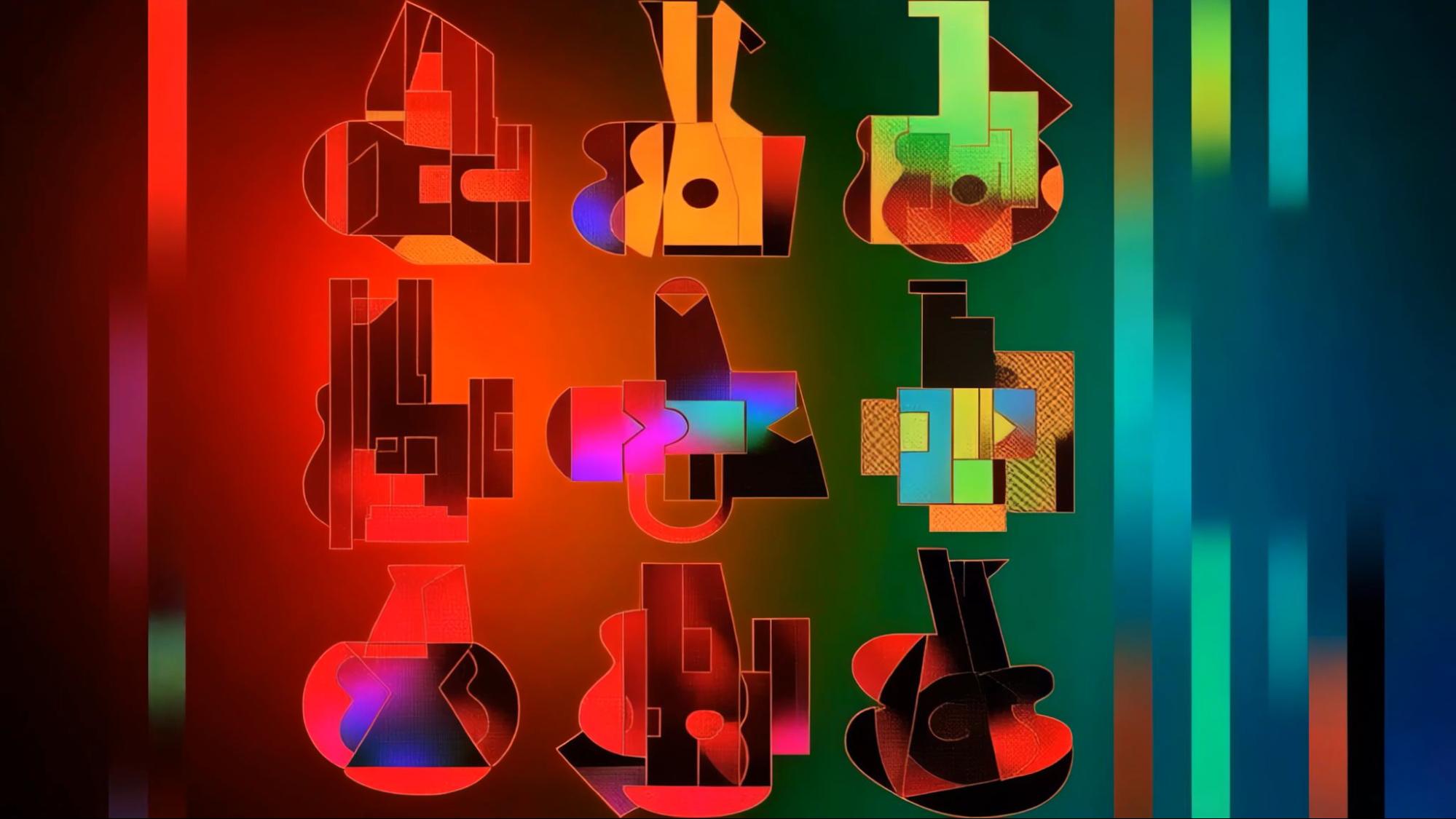

P: Your Sedition release Picasso Pizazz reimagines Picasso through digital vectors. What drew you to return to Picasso in this format, and what does digital vectorization allow you to achieve that painting or even analogue collage cannot?

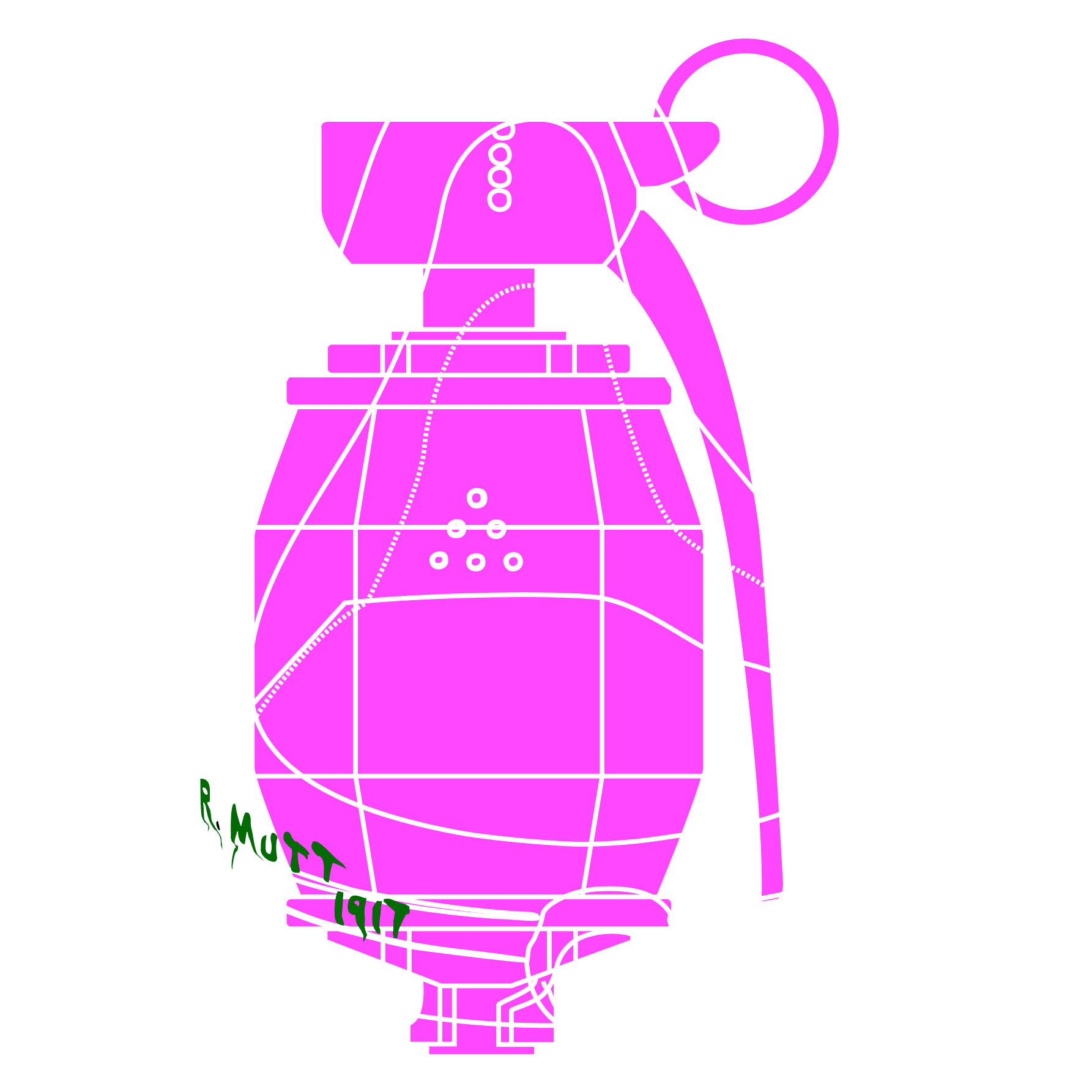

Nick Fudge, Il n’y a pas de solution parce qu’il n’y a pas de problème, 1994–

N: I didn’t return to Pablo Picasso to pay homage so much as to solve an unsolvable problem. I interpret his legacy as the 'Picasso Problem'. As a painter he seemed to have done almost everything, and in his late works he reworked Manet, Velázquez and others in a way that anticipated postmodern strategies of repetition and appropriation. This meant that later artists such as Pollock, Gorky, de Kooning, and Condo felt they had to work through his archive to break free from his influence to find their own voice.

My title “Problem of Picasso” is therefore somewhat ironic, and is partly inspired by these male painters’ struggles with Picasso’s legacy and with my long-standing interest in Marcel Duchamp and his excoriatingly sceptical claim that “there is no solution because there is no problem.” Picasso is both the apparent problem and, at the same time, a reminder that there may be no final problem to solve. As the art historian Christine Poggi has suggested, he often treats style not as a private, subjective signature, but as a shared cultural code that can be picked up, reused and put back into circulation. I more or less taught myself to paint by obsessively studying his work before I went to Goldsmiths, so I absorbed that lesson very deeply.

“ I began to think of art not as a single ‘original’ style, but as something built from existing visual languages — and later I carried that way of thinking into the digital realm. The push and pull between Picasso’s huge influence and his own use of borrowing and remixing runs all through my work.”

Early on, in the mid-1990s, this became very concrete in the form of icons. I started building my own “operating system” on the desktop: custom folder icons based on well-known artworks – Jasper Johns’s Flag, Vladimir Malevich’s Black Square, Picasso’s Swimmer and self-portraits, works by Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Sonia Delaunay, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Hanne Darboven, Duchamp and others. Each icon did two things at once.

Nick Fudge, Three Desktop Folder Icons (3 of 70+ vector folders in the Digital Boîte-en-valise), 1994–ongoing.

On a practical level it was just a folder; on another, it was a tiny image that pulled a strand of art history into the logic of my digital archive. The process was simple but generative: I would make a small vector copy of a painting and use that image to customise a MacOS folder icon – Johns’s Flag, Picasso’s Swimmer and so on – so that these appeared as the folders on my desktop. On the surface they looked like art icons; one click on that small picture opened into a folder containing my own related files, sketches and works-in-progress. Those larger works could then feed back into new icons. So there was a constant movement from micro to macro and back again: from a 32-pixel symbol on the desktop to a complex vector composition, and then back to a new icon derived from that painting. Each customised icon became a small story or sign hidden inside the interface, a discreet language of symbols that tacitly referred back to the larger operating system of the computer itself.

Over time I began to think of each icon as part of a private visual language. A folder didn’t just hold files; it represented a particular line of inquiry and created hinges into specific ways of thinking. The Digital Boîte-en-valise – my term for this portable digital museum – now includes more than seventy such folders, each with its own vector emblem, and it’s still growing. Instead of a neat tree of files, the structure functions more like a visual, associative map that lets me jump between different strands of the work: from a tiny icon to installation-scale composition, from a finished work back to its folder, from painting-thinking to interface-thinking and back again.

Picasso appears in the Digital Boîte-en-valise system in many guises. I first made icon-scale versions of his self-portraits and paintings, then moved on to more elaborate vector pieces, such as my reworking of his 1901 self-portrait Yo—el Rey (“I am King”), which later fed into the Picasso Pizazz

Nick Fudge, YP1901_01_3_2 (After Picasso), detail, 1994-

works on Sedition. My interest in making such a close copy was analytical rather than nostalgic. Using vectors, I could track and reconstruct the individual strokes with which he painted his own face – the marks that build the surface of the painting. One of the surprising things about making an almost exact copy is that you end up stepping inside the other artist’s process: you follow their decisions, stroke by stroke, and try to understand why a mark sits exactly where it does. With the 1901 self-portrait, you sense both the rawness and the precision of taking apart representational portrait painting and rebuilding it as something sharper and more direct. Translating that into vectors meant examining those choices in detail. In that sense, the process let me tune into his intuition while still working entirely within my own medium.

Vectors also let me do things that painting or analogue collage can’t. A vector stroke is endlessly adjustable and repeatable: it can infinitely be scaled up or down, recoloured, remapped and reused across a whole series without losing clarity. That makes it ideal for what I think of as “simulacral” paintings – works that look like they are made of paint but are actually constructed from pure digital geometry. In my vector piece YP1901_01_3_2 (After Picasso), every thick, raised brush mark is simulated, yet the physical “hand” is hidden. On a screen, it can pass as a faithful copy, and many viewers may not realise they’re looking at a hand-constructed drawing made entirely from vectors. That invisibility interests me. It means the piece operates on two levels at once: as a close study of Picasso’s painted surface and as a digital object that belongs to the larger system of files, timelines and themed folders it came from – and feeds back into.

Nick Fudge, Machine of Connectivity and Undo (Apple Newton MessagePad 100), 1994–2015

Across my archive, Picasso functions almost like a style dataset. I make digital approximations of his recurring motifs and ways of building figures – for example in my Picasso_Problem_Seated_Woman series, where I reconfigure a seated figure using Illustrator’s transformation tools to generate new variations. These works explore things like the materiality of digital tools and spaces, the history of images on screens, to the hidden design of interfaces. Picasso Pizazz is one node in that larger network. By rebuilding a Picasso self-portrait with vectors, I can treat his legacy not as an obstacle that blocks new work, but as flexible material I can compress, expand, reroute and test in digital space. Vectorisation doesn’t just reproduce Picasso; it lets me turn the so-called “Problem of Picasso” into a working method and use his visual language to think about how painting might evolve when it becomes a pure virtual structure.

P: In your previous interview with Sedition you described adopting the modernist principle of medium specificity and applying it to digital material, insisting that digital art remain strictly digital. How has your understanding of digital medium specificity evolved in the 2020s, especially as AI, cross-platform hybrids, and post-medium practices blur boundaries more than ever?

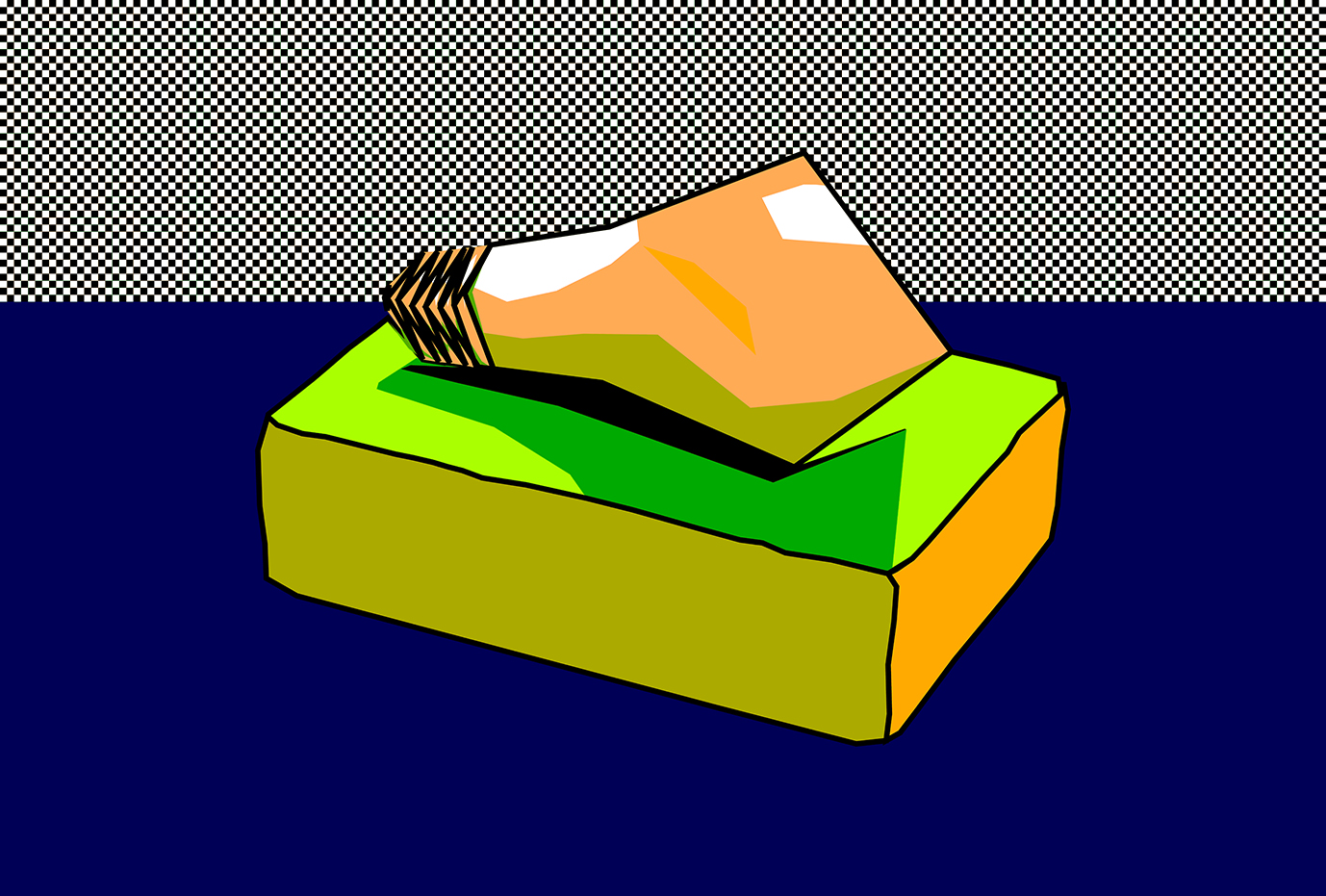

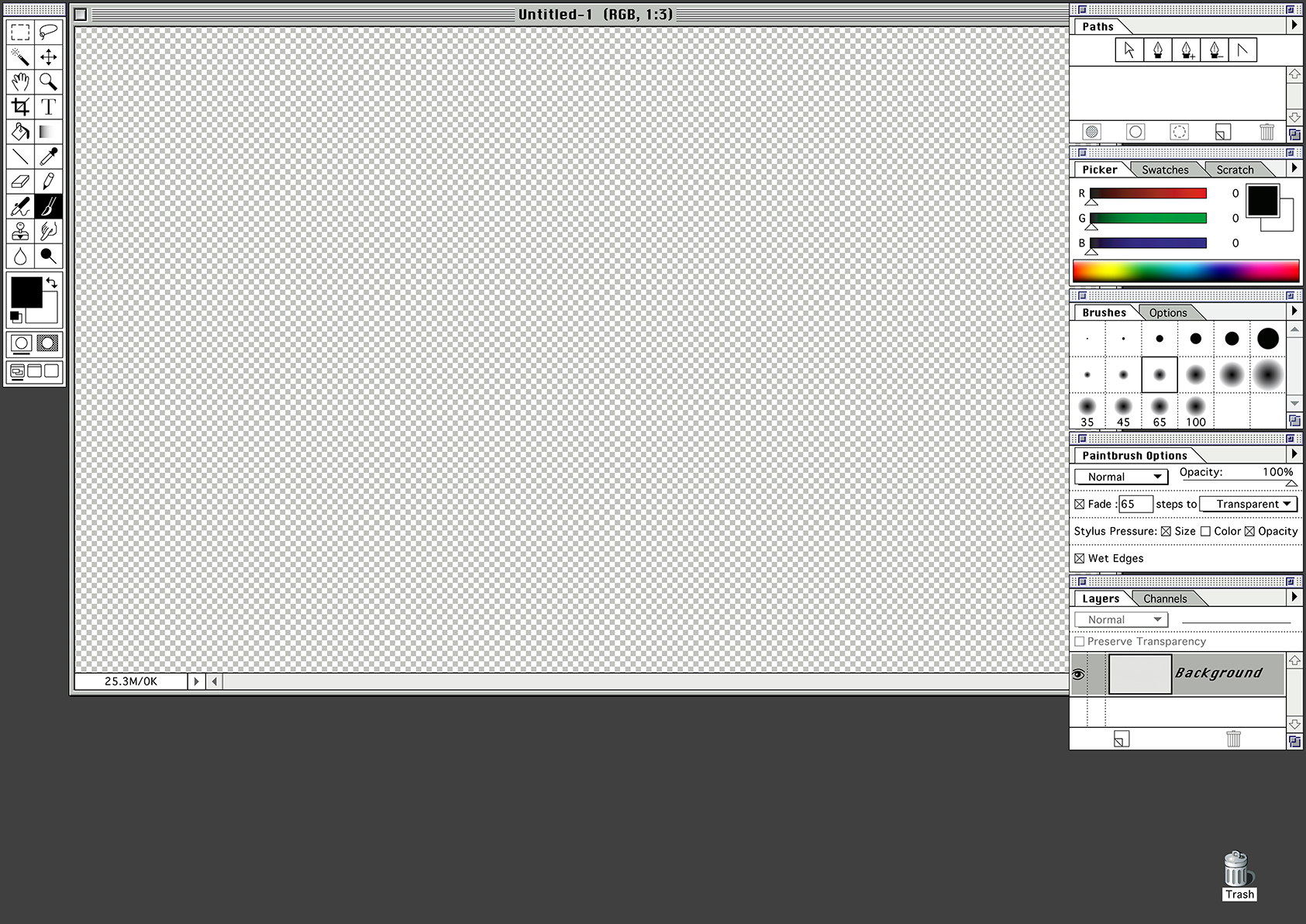

N: When I first spoke to Sedition about medium specificity, I talked about my refusal to output digital work into physical formats. I felt that digital work should remain true to its virtual form. When I first started working on the Mac (System 7.5 and above), it was still very much the postmodern moment, when artists were considering about how each medium communicates its own internal logic (Clement Greenberg's, Art and Culture: Critical Essays, and Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message, for example). What interested me most about digital medium specificity was how each software update changed the way images could be created. Every couple of years, a new version of Photoshop or Illustrator would be released with tools that, although initially designed as analogues for traditional studio tools, began to surpass the capabilities of traditional media.

For instance, the introduction of the Layer Palette in Photoshop 3.0 featured a transparent background layer with a checker-board grey and white pattern that created a sort of vacuum for the image to be edited upon. For me, this wasn’t just about introducing a useful feature; it offered me the possibility for entirely new ways to create images. Suddenly you could work on different levels of an image at once, toggle them on and off, and let them interact - something you could not easily do in painting or photography. For me, this new feature became a conceptual tool for transparency itself – as a way of making visible the thinking processes that, in painting, are usually hidden beneath the ‘finished’ surface. Also, I began to think of the transparent background layer as an abstract space to explore the illusory nature of reality depicted in images. Plato describes this kind of abstract space of creation in Timaeus as a third kind of space – a place that “provides a home for all created things” that at the same time is “hardly real”... meaning that beneath representations is essentially nothing.

Nick Fudge: Screenshot showing the first time I made a pattern to create a transparent ground, 24, April, 1995

Nick Fudge, AP_v3_Chrome_Space_3_macOS_8, 1994-

At the same time, I found myself asking: where are these updates going? What is the “end point” of a digital brush, or a layer, or an undo function? When a brush is virtual, its possibilities expand far beyond anything a physical brush can do. The history brush (Photoshop 5.0), for example, lets you paint backwards in time and selectively undo parts of an image – something unimaginable in oil paint. I saw in these tools the possibility of making a representation of a representation (or a copy of a copy) - where we can see the process of imaging itself. Furthermore, rather than thinking about the content of an image, I began to think more about the palette layers, timelines and vector maps as both digital painting tools and as the ‘image’ of the digital itself - and this is what I wanted to communicate.

From 2022 to now, updates have now become simultaneous and ‘organic’ - where a user prompt initiates the AI to update the medium in question within seconds - learning from itself continuously. AI has made identifying and visualising digital tools ever more complex. As a conceptual artist - AI offers an ‘infinite imaginary’ which has the potential to become dystopian if we surrender our imagination to machinic imagination - where they process creative imagining for us - as philosopher of technology Yuk Hui argues is where we are headed. This is the elephant in the room. How do we deal with this problem? This is why I would argue that critical thinking plays a crucial role within the artistic/creative collaboration with AI - as we risk outsourcing our own creativity while participating in the colonisation of creativity on a global scale.

This has made things harder and more interesting at the same time. Now that AI has entered the studio; images travel seamlessly between platforms; artistic practice now shapeshifts between video, installation, performance, NFTs, print, biological material, you name it. My way of maintaining my

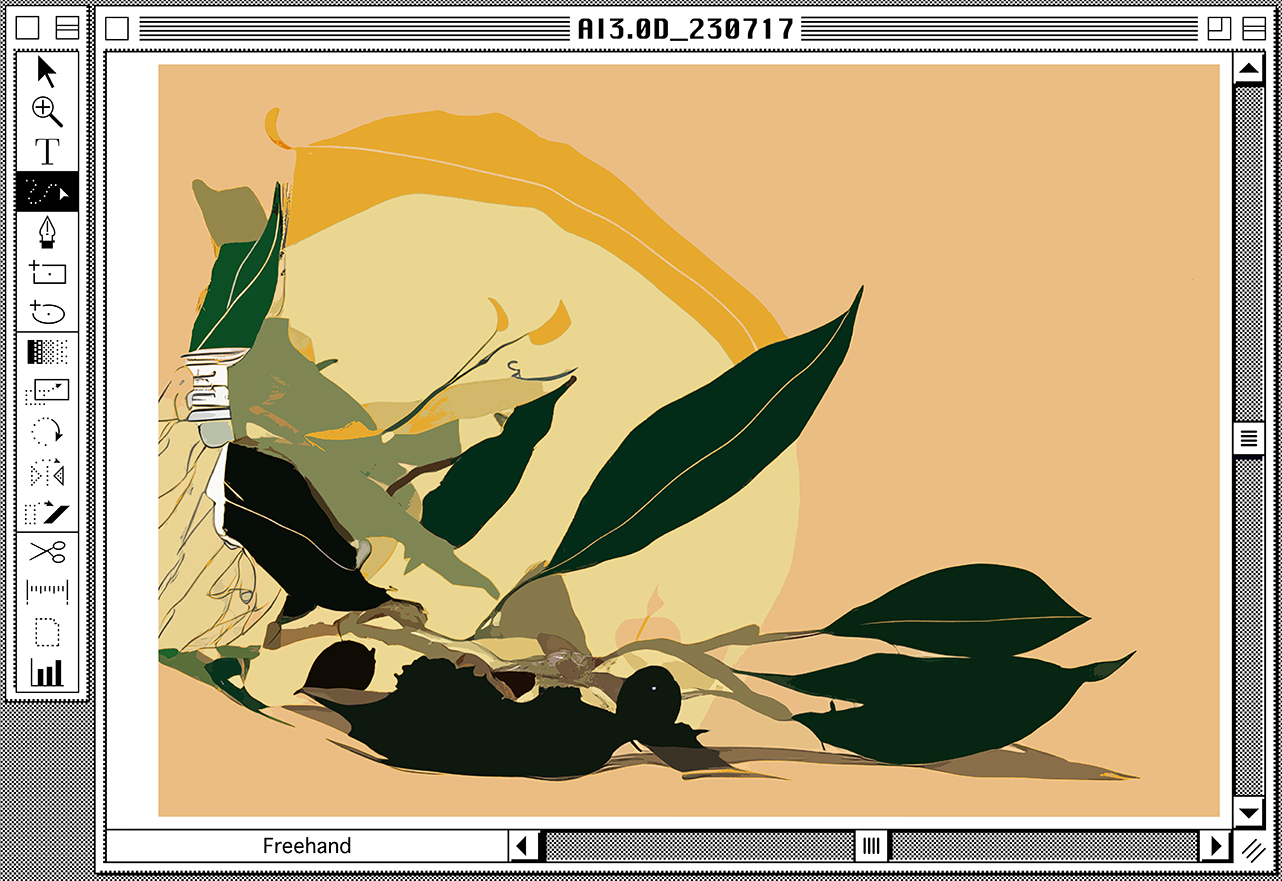

Nick Fudge, Adobe Illustrator version 3_Virtual Still Life-1994-GE17-9-23

own creative autonomy (as I have done my whole artistic career) within the vast complex that is AI is that I don’t use it to generate arbitrary images. I use it to intervene into my existing archive, to rewrite early files from the 1990s using contemporary tools as a source for multiple outputs (this is discussed in greater detail in the last question). As I mentioned in the previous question, the Digital Boîte-en-valise is its own system of files and folders, but aspects of it can be sent out into the world under very different guises using AI: a screen-based work on Sedition, a large-scale projection, a secret digital intervention in Lop Nor desert, a digital work that challenges the possibility of it being seen at all. So I no longer think of medium specificity as ‘purity’.

The question for me now is: what is essentially digital in a given work, and how do I keep that legible even when the piece moves into other forms?

So my understanding of digital medium specificity has changed alongside the medium. I still resist the idea that digital work has to be validated by becoming a painting or an object, however, I also believe in rarity and uniqueness - so I am okay with developing multiple strands of outputs as long as they are strictly limited in terms of concept and the meaning of the media used. What hasn’t changed, from Goldsmiths to Sedition to AI, is the underlying gamble: to keep testing what freedom might look like for an artist working with digital material in a culture that wants everything to be instantly visible and easily owned. The Digital Boîte-en-valise is one answer to that question – a system that can stay partially hidden while sending out signals in different directions: a vector file on a hard drive, a Sedition edition on someone’s phone, a projection in a gallery, a microscopic inscription in a lab, a work that exists precisely by resisting being seen. If there’s a thread that connects all of this, it’s the attempt to stay honest about what is essentially digital in each piece, while still allowing it to travel, transform and sometimes disappear. I don’t know exactly where that will lead, but I’m interested in

Nick Fudge, Herlequin-GE-2024, 1994–

the idea that an artist’s “legacy” might not be a stable body of work so much as a set of evolving structures – a living archive that continues to open new routes for seeing, thinking and making, long after the first files were created.

These artworks by Nick Fudge are now streaming on Sedition worldwide and can be found on the “Curated by Aria” channel.

Artworks to Pair With the Article / Content Series