Sedition's Community Manager Vladislav Alimpiev had the pleasure of interviewing ![]() Marina Zurkow ahead of her inaugural launch on Sedition. Learn about her extraordinary journey from this discussion.

Marina Zurkow ahead of her inaugural launch on Sedition. Learn about her extraordinary journey from this discussion.

Q: Could you please introduce yourself and your artistic practice to Sedition’s audience?

A: My name is Marina Zurkow, I'm a media artist, and I've been focused on environmental issues since 2006. I would describe these as issues that Donna Haraway called "natureculture” entanglements and what systems thinker Russell Ackoff coined as "wicked messes:" that in the pursuit of solutions to complex, systemic problems, we often birth new problems.

My art invites people to think and feel the complexity of the environment, challenging the human tendency to view ourselves as separate from nature's systems. My work varies in form; I'm known for my software animation, but I also collaborate on diverse projects ranging from AI-prompted image-making to guided sensorial audio experiences, and even dinners focused on our relationship with climate change through food. I believe that art can serve as a tool to challenge our anthropocentric perceptions, make us feel more like the earthlings we are, and foster more profound connections with our environment.

Q: Can you tell us more about your work on ocean-focused issues?

A: I began focusing on the ocean in 2013, inspired by Stacy Alaimo's essay, "Violet-Black.” Despite being called "Earth," our world is over 70% ocean, a space we can't comfortably inhabit for long durations. But before I could get into the ocean’s depths, I encountered its near-solid surface of shipping routes; I was up to my neck in shipping logistics and how the 'Buy it Now' button, for example, opens Pandora’s box, unleashing an army of events in the world that contribute to environmental issues. I spent two years translating logistics into visible forms that would resonate with people. In 2016, I began thinking more about ocean depths and exploring our varied and often conflicting perceptions, ways of knowing, and imaginaries.

Q: You mentioned working with chefs to create food experiences around climate change. Could you elaborate on this?

A: Supported by LENS (Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies), chefs Hank and Bean and I developed “Rising Seas Jellyfish Jerky,” a pop-up snack shack on the UCLA campus. Jellyfish are predatory animals that do well in disturbed ecosystems and have become a symbol of climate change for us. The jerky was seasoned with spices from regions at risk of sea level rise. The food was a way to start a conversation and put these ideas into people's mouths, literally and figuratively metabolizing climate change.

Q: Your art often explores human, nature, and technology interactions. What first drew you to this theme?

A: What drew me to technology was the seductive nature of animation and the early Internet. I began animating in 1994 with gifs and then Macromedia Flash 1.0; the bright colors and moving characters of cartoons allow viewers to drop their prejudices and biases, making them more receptive to challenging topics. As for the environment, my interest was sparked by experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand. In 2005, my studio in Brooklyn started flooding due to increased rains in New York, and hurricane evacuation maps were issued that year, bringing climate change home as a very present reality. This realization and the release of Al Gore's film "An Inconvenient Truth" marked a significant shift in my work toward environmental themes.

Q: It’s evident that extensive research goes into creating your work. How does research influence your art?

A: My research doesn’t necessarily lead to didactic pieces of art. Instead, research activates gut decision-making in my work. My hope is that my artwork is primarily received as an experience to be sensed. While my decisions are based on extensive research, they are intuitive rather than systematic or directly illustrative of my research. If the viewer is interested, plenty of supplementary material is available to engage with, which can dimension and amplify the questions and intentions of the artwork.

Q: How do you hope audiences engage with your art?

A: I want audiences to be immersed, and for them to slow down. Many of my art pieces are generative and run on probability, offering the audience a sense of being inside something ever-unfolding, with punctuation points that disrupt the durational, meditative cycles. Ideally, viewers live with the art and slowly unravel the relationships within the pieces over time.

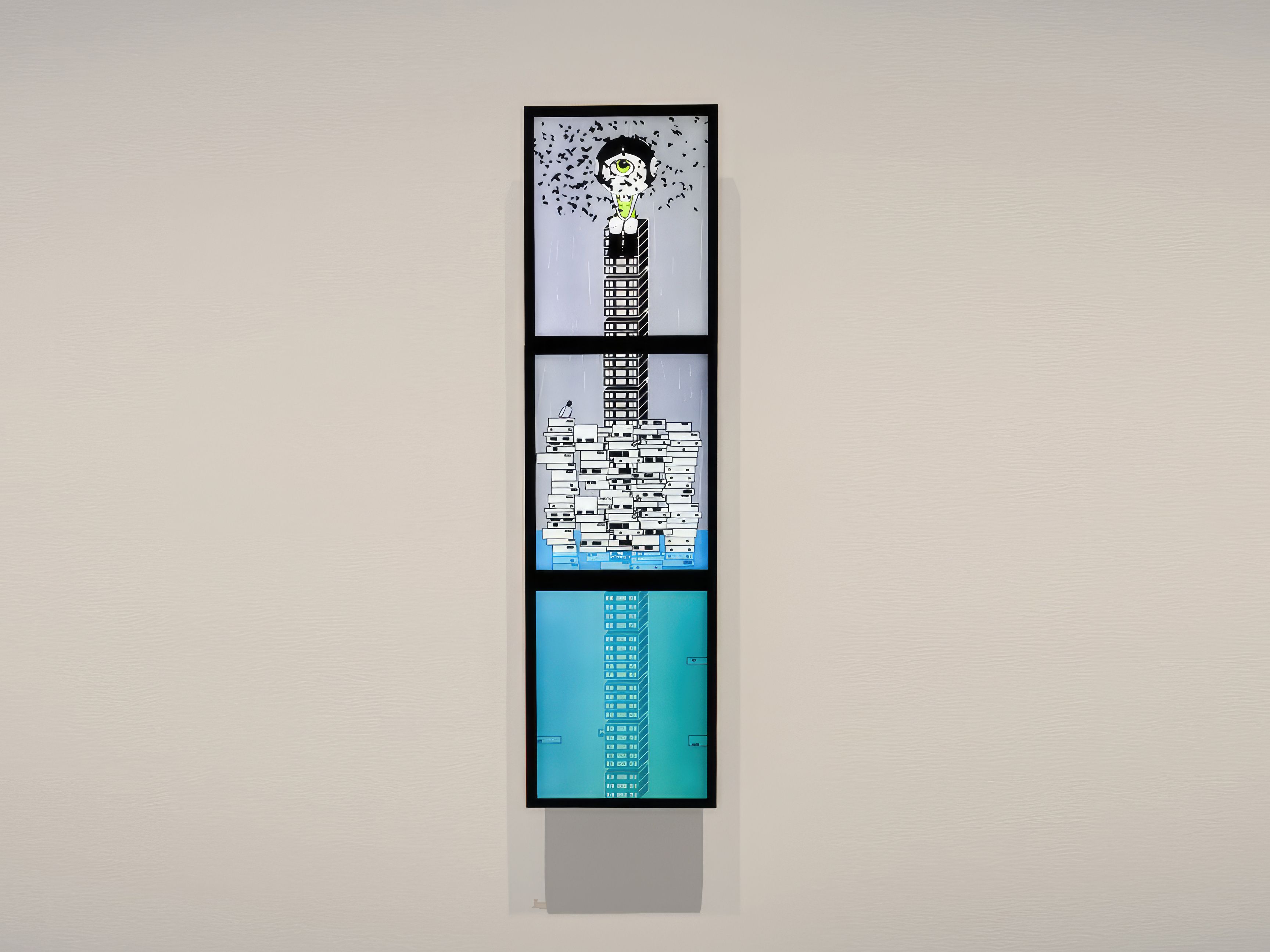

Q: Could you talk more about your concept of Liquid Ways of Sensing, your first collection on Sedition?

A: The collection is part of a larger project called Oceans Like Us, which I reflected on already. The concept loosely focuses on different ways of knowing the ocean: from our reliance on sensing devices and measuring instruments to understand currents and track phenomena, to the sensuality of motion, light refraction, to the fantastic and unknown ways in which the ocean is imagined and possibly experienced by its inhabitants. I'm interested in creating an oceanic environment in which these elements coexist in all their contradictory desires and forms.

Q: How has your creative process evolved over time?

A: Over the years, I have refined the ways I work, trusting my intuition while fueling it (and sometimes challenging it) with empirical study and research (texts and interviews). I deeply value the element of surprise that arises from creating generative art or working with AI, and moved away from the need to control a timeline or a composition; I now embrace the speculative, open-ended, and imaginary. The need to be declarative originated from my training in semiotics and postmodernism, where generally speaking, culture was reducible to language, so it has been really mind-expanding to offer up questions and synthesized experiences that exceed explanation. And to live with—and continue to work with—contradictions.

Q: What challenges do you face in your artistic journey, and how do you overcome them?

A: The biggest challenges are financial and temporal. It's about securing time and resources to explore and grow, not just meet deadlines or complete tasks. Navigating the scarcity economics prevalent in the art world is one of the hardest parts of being an artist.

Q: What are your thoughts on recent technological developments like NFTs and AI in the art world?

A: Neither NFTs nor AI are a fad, but they both raise serious ethical concerns. I resisted participating in NFTs at all, in significant part because it was environmentally unsustainable, but not only that. The recent boom of NFTs, in which art was considered a trading currency, contradicted my principles that art isn’t reducible to its monetary value, nor should it be built on a model dedicated to hoarding or scarcity. Meanwhile, AI raises questions about authorship and the ethical implications of folding living artists' work into the datasets without their permission. It's crucial to develop individual ethical frameworks to interact with these new phenomena and also push companies profiting from them to operate ethically.

Q: What are your thoughts on Ethereum? I know you don’t seem to favor it from our previous conversations; may I ask why?

A: When it comes to Ethereum, my issues stem from the environmental implications and the broader impact of these technologies. The digital world isn't confined to just what happens inside the computer. For example, when people suggest that much of the energy used in the proof-of-work came from renewable sources, they overlook the true cost of renewables.

Renewables aren’t free; they're better than fossil fuels but still require significant resources. Solar panels, a relatively green solution, are made from materials that have their own environmental costs. The notions of "free nature" or “free energy” are completely misleading.

In my view, the problem with our approach to matters is that we often don't step outside of our own frameworks. We become focused on doing our work the best we can without asking broader questions about how the systems we participate in could be different. I learned a lot about systems thinking from Howard Silverman, and it's taught me to take a bird's-eye view on issues.

Q: You mention the waste produced by technology. Can you elaborate on this?

A: Yes, as an artist and an educator, I consider the waste I produce and its impact on the world. The question that often comes to mind is whether the production of culture, thought, and consciousness offsets the actual material costs of what and how we make.

We should always question why we’re reproducing systems that already have significant environmental costs. This is a critical question when it comes to virtual currencies, which (to some extent) reproduce the concept of fiat currency but in a digital form.

Q: What's next for you? What projects are you currently working on?

A: At the moment, I'm working on several projects. I'm co-authoring a speculative manifesto for a multispecies labor union. I'm developing a long-form guided audio experience about the "sixth sense" that fish have - called their lateral line. I'm also working on a series of AI-generated images about death.

In addition, I have an ongoing project with digital media artist Sarah Rothberg. We've created a game framework, Investing in Futures, to help people imagine worlds they want to live in. We're working to bring this framework to museum, community, and academic contexts.